My Story:

Traci's Story

There are two sides to every story

We’d always known that Ben would need a liver transplant at some point, but it was still a huge shock when doctors casually said at one appointment that they thought it was time for him to go through the testing.

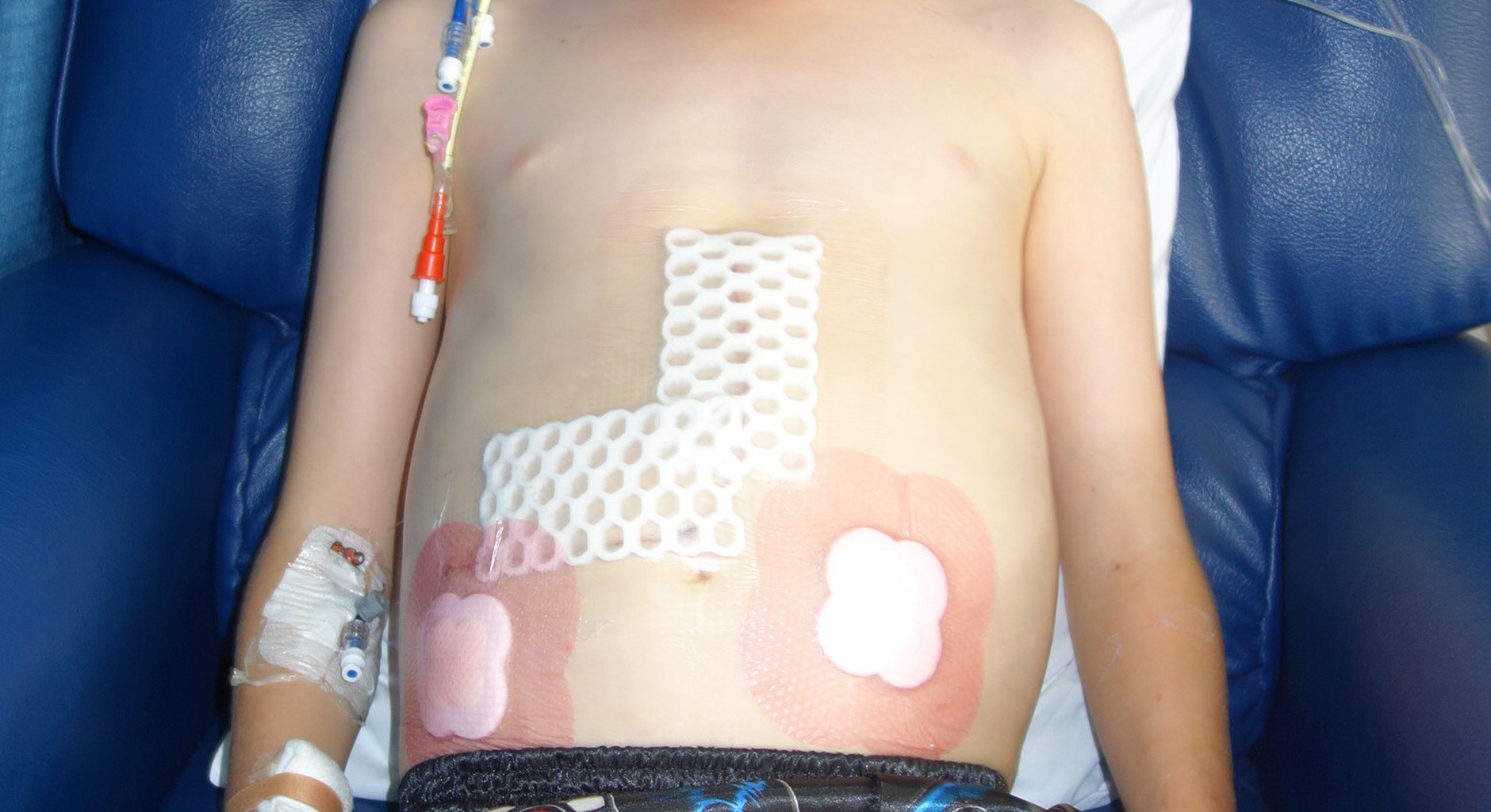

We’d always known that Ben would need a liver transplant at some point, but it was still a huge shock when doctors casually said at one appointment that they thought it was time for him to go through the testing. His transplant workup consisted of twenty-four appointments in five days and culminated with him going on the deceased donor waiting list. He was nine years old.

The five months on that waiting list sometimes sounds short, but at times felt very long. Every time a rescue helicopter flew overhead, we wondered if the person would survive or if they might be an organ donor and it would be our ‘turn.’ It’s a real quandary, wanting to wish people well, whilst knowing that Ben and over 500 other people were waiting for organ transplants. One random Monday night we got the call. It was suddenly very real. We had forty minutes to sort everything – another child, a cat, house, school, work, clothes, life as we knew it. But from the moment we got on the plane to Auckland it was calm. There was nothing else we could do, this was it.

Early the next morning Ben’s surgery went perfectly, and from there everything else fell into place. Prior to the transplant the medical team told us so many possible outcomes but at one point said, “we’ll never tell you best case scenario because it never happens.” Somehow that was us. Just a week after his transplant Ben and I moved into our transplant room at Ronald McDonald House Domain. We had appointments at the hospital most days and he had school visits a couple of times a week but otherwise it was just us, isolated from the world in our room.

We’d been there about a month when a friend went to Australia. Ben’s response was “well I’m on holiday too.” I know he’s resilient, but to think you’re on holiday when in fact you’re in isolation after a transplant? I put it down to how well he was finally feeling. The weight of illness had been lifted thanks to the ultimate kindness from a complete stranger.

The other side of the story…

While my son received a life-saving transplant, someone’s family was grieving. Within a few hours their own child went from fun-loving and carefree to being a brain-dead organ donor. How incredibly hard it must have been for them, yet they chose to save the lives of up to eight other people.

Only one percent of all deaths in New Zealand can be organ donors. They need to be in a hospital, in an ICU, on a ventilator, and suffer either brain death (irreversible cessation of all brain activity) or circulatory death (irreversible cessation of all circulatory and respiratory function). The most likely causes of death for organ donors are a brain bleed, trauma (including road accidents), prolonged lack of oxygen often from stroke or cardiac arrest, or ischemic stroke (cut off blood supply to the brain). Donation is discussed with all families irrespective of whether the word ‘donor’ is on the driver licence and the family makes the final decision. If the person has ‘had the conversation’ about organ donation with their family, it makes it a simpler and less traumatic decision for the family in their time of grief.

Donor coordinators provide information and support for donor families both before and after organ and tissue donation. This includes the offer of items of remembrance such as handprints and locks of hair, providing general information about the outcome of their donation and facilitating anonymous communication between transplant recipients and donor families and vice versa. In 2022 there were just 63 deceased organ donors, the lowest number in five years. But those 63 heroes saved the lives of 184 people who received lifesaving kidney, liver, lung, heart, or pancreas transplants. Another 44 people received eye tissue, heart valve tissue or skin from these donors. Of these heroes, 62% were male and 38% female. The youngest donor hero was just 14 years old and the oldest was 78. Seventy percent of donor heroes in 2022 were Pakeha, with Asian, Māori and Pasifika making up the rest. It’s a close representation of our diverse population. New Zealand sent four organs to save lives in Australia and received seven back. It’s all a matter of timing and matching. There were also 70 living kidney donors and one living liver donor hero in 2022. Most living donors recover in six weeks and most find their recipient recovers much faster, because it’s been so long since the transplant recipient felt healthy. The transplant literally saves their life. Each year there are about 7 living kidney donors that altruistically donate to a complete stranger. These people are super important because they often set off a paired kidney exchange chain of multiple people who have a living donor that doesn’t match them. Altruistic donor A donates to recipient B, donor B donates to recipient C, donor C donates to recipient D. This is a very simple version, and there are many people waiting for an exchange match, with the database run monthly looking for matches. Organ donors are heroes. There are no other words. Such a selfless act needs to be thanked, but words can’t convey your appreciation. Because of someone’s selfless gift of life, my son turned 18 this year. He’s graduating school, choosing a career, and planning to travel.

He’s making the most of his second chance at life. But I understand that there was an empty place setting at someone’s Christmas table, and that they are likely still grieving. From my side of the fence, I can’t fathom being posed the question of whether you want to donate your loved one’s organs. Personally, I’ve always been a donor but being asked to make that decision when hope for your loved one is gone must be heart breaking.

I commend the medical teams and their support staff for all they do for donor families. I wish we had higher donation rates in New Zealand. And I wish our transplant waiting list wasn’t growing each year. As a country we should do more to recognise donors, both living and deceased, for the massive impact their decision has on the lives of recipients, their families, and their friends. Organ donation should be talked about, it should be discussed at the dinner table, and we should all know our loved one’s decision, whatever it may be. As for thanking our donor’s family, maybe the real thanks is what you do with your second chance. My son got his second chance. To his donor and their family, and to all donors in New Zealand and their families, thank you.

Traci Stanbury, Christchurch.